Powered by RedCircle

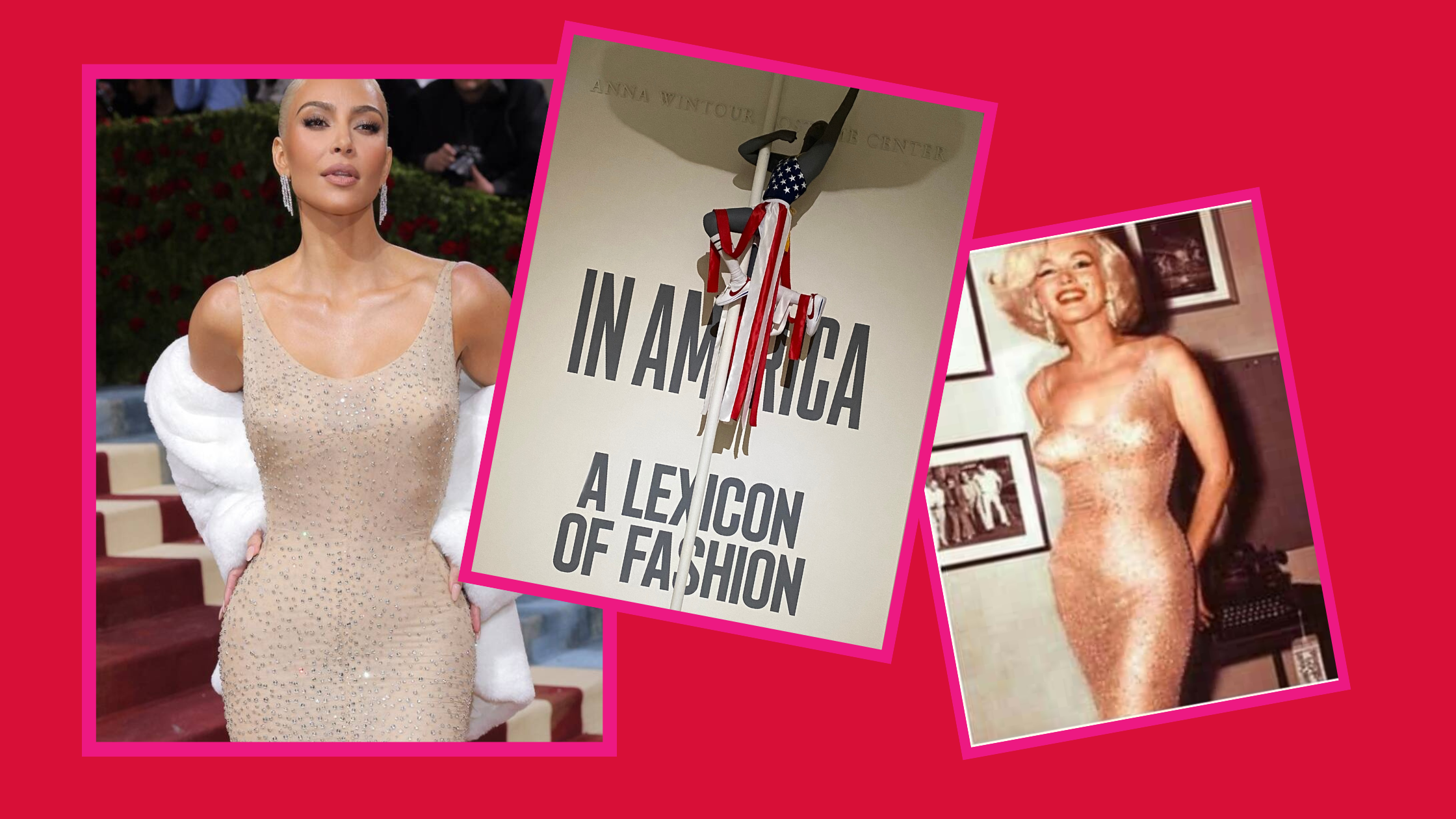

If you follow me on Instagram, you’ve probably noticed that I, too, have entered the intense debate about Kim Kardashian’s wearing of Marilyn Monroe’s 1962 dress for the Met Gala last week. In fact, not one—but two!—videos that I created on the subject went viral. And while there are many layers to unpack behind the whole situation, I decided to focus on the conservation-related side of it.

With the thousands of views and likes also came several comments, which have opened so many questions and personal reflections about fashion, museums, and the whole point of fashion being in museums… especially in Abya Yala!

I think at this point most of us realize that fashion exhibitions have become widely popular throughout the globe in the past decades. In English-speaking contexts, this has resulted in the development of a sub-field of fashion academia dedicated to fashion curating, conservation, and museology. Formal education programs, publications, and conferences on the subject have also increased.

But things are quite different in Abya Yala.

Exhibitions of fashion are still somewhat rare and our general exposure to them is, in many cases, almost entirely virtual and mediated by what other people have to say about them. So while we know of the existence of blockbuster fashion exhibitions in museums like The Met in New York or the V&A in London, only a privileged few get to visit and experience them in person. And while fashion has been exhibited in Abya Yala for decades (or longer), the concept of fashion curating still seems somewhat foreign. [1]

In fact, fashion curating is most often invoked in reference to fashion weeks, trade shows, and concept stores, than in the context of museums, galleries, and other cultural spaces in Abya Yala.

And this, I believe, has had a huge impact on how we perceive fashion as a subject of study—and even on how we interpret the whole Kim-Kardashian-in-Marilyn-Monroe’s-dress debacle.

While I saw quite a lot of content on the topic from dress conservation perspectives in English, I didn’t really see much of this being debated in Spanish—which is why I decided to share my videos. Once posted, several comments accused me of being too dramatic about nothing important, claiming that the garment in question was “just a dress.” These reactions struck me, as it seemed to me that the debate on conservation was met with less resistance in the English-language posts that many of my colleagues had shared.

The question of whether or not fashion should be preserved in museums is a complicated one. Also complicated is a consideration of which kinds of clothing should be preserved and which can be worn over and over again—especially with the rise of second-hand and vintage shopping in recent years.

But one thing is clear to me: fashion is never “just a dress”—or any other type of garment, for that matter. Fashion is a mirror of the society in which it emerges and it simultaneously reveals and shapes many of the internal values, ideals, anxieties, and dynamics of that society.

Specific garments, therefore, act as repositories of human history, carrying the traces of the people who wore them. At the same time, garments showcase particular moments in the history of design, which is, in turn, inextricably linked to the “bigger” social, cultural, political, technological, and ideological histories of humankind.

That’s why it’s so important to preserve historical garments!

And this, I believe, applies both to “exceptional” garments, such as Marilyn Monroe’s dress, but also more mundane pieces that can tell us about the everyday lived experiences of “ordinary” people. (I spoke more about this in a Live session hosted by Culturas de Moda on Sunday, if you’re interested in a more detailed consideration of the matter.)

But the fact that original garments from different time periods contain so much of human history seems a bit foreign for many people in Abya Yala. Some other comments on my videos specifically mentioned the fact that we already have photos and videos of Marilyn Monroe wearing this dress so it doesn’t matter if the actual dress ceases to exist.

And I wonder if this might have to do with our limited exposure to exhibitions of fashion—and perhaps also to the fact that we’ve become used to having to draw upon pictorial and written sources more frequently than garments themselves when writing our histories of fashion. This is precisely a result of the relative scarcity of extant historical garments in Abya Yala when compared to Europe or North America.

When I shared these thoughts with Vicky Salías, director of the Dress History Museum in Buenos Aires, she told me that there had been quite an intense debate on the subject in Argentina. We also talked about the Fashion Museum in Chile, which openly rejected Kim Kardashian’s wearing of Marilyn Monroe’s dress on an Instagram post.

Vicky also mentioned the fact that there are relatively few fashion museums in Abya Yala and posed the question of how this might impact a more general perception of dress collecting and conservation in our region. The fact that the need to preserve Marilyn Monroe’s dress was more vividly discussed in Argentina, where proper fashion museums exist, than in Colombia, where we only have incipient “regional costume” museums, might point to a direct correlation between the two.

And this made me think about a 2008 essay written by Dr. Valerie Steele, director and chief curator of the Museum at FIT, on the rise of fashion exhibitions. Steele suggested that there might be different levels of “education” among visitors to fashion exhibitions in France and the United States. These differences are likely based on the accumulation of cultural capital built from the level of collective exposure to these kinds of displays. However, Steele argued that a lower cultural capital is not an excuse to curate “dumb” and simple fashion exhibitions in North American museums. Rather, it should be the motivation to create exhibitions that are “accessible on a variety of levels” and prove that fashion is a “serious” subject of study. [2]

If North American audiences are undereducated in the presence of fashion in museums, the case is even worse for Abya Yala! But I want to extend Steele’s contention that this is no excuse to curate mediocre exhibitions or to simply ignore Kim Kardashian’s dress choice for the Met Gala.

The unanswered question here remains how to build up our cultural capital around conserving, curating, and exhibiting fashion in a context where fashion museums are still scarce and where fashion exhibitions, when they appear, are not even curated by experts in the matter.

My answer—as almost always—has to do with opening more spaces that foster public-facing discussions on subjects that have until now been limited to a few. Social media, blogs, newsletters, and podcasts are key.

But so are institutions and museums.

And we still need to find ways to reconcile the two.

As in many other parts of the world, fashion exhibitions in Abya Yala are experiencing momentum. And fashion curating in the museum field is slowly but steadily developing in the region. So, as we continue to imagine what exhibiting fashion might look like in Abya Yala—and the rest of the world—we need to foster conversations between institutions and individuals, professionals and the general public.

Thank you, thank you for reading!

Until a next time,

—L🩷

**The background music is “Expression d’une presence indéfinissable” by Koi-discovery (2022), used under Creative Commons Licence with attribution 4.0 (CC BY 4.0).

Notes:

[1] I have explored the development of fashion curating in the region in more academic settings, including a fantastic conference on Curation and Conservation organized by the Association of Dress Historians and La Venaria Reale in Torino last year.

[2] Valerie Steele, “Museum Quality: The Rise of the Fashion Exhibition,” Fashion Theory 12, no. 1 (2008): 15.

Leave a Reply