This month I’m focusing on fashion history as the subject of my fashion musings. Sounds like an obvious choice for a fashion historian, but I must confess that I don’t think about fashion history as a subject all that often. In fact, it somehow seems that I only get to do it whenever I’m going through some sort of professional or personal crisis that makes me question my life choices—my career as a fashion historian being one of them.

But if I were to go back in time, I probably wouldn’t choose a different career path. And, while it might sound a bit romantic, I do believe that fashion history has a huge potential to help us redress global fashion to create more truly sustainable, equitable, and diverse alternatives. The key, of course, is to diversify fashion histories so that they reveal the many expressions of human creativity and the close relationship between fashion, colonialism, and systemic oppression. (But more on that next week or in Patreon if you’re subscribed to early access.)

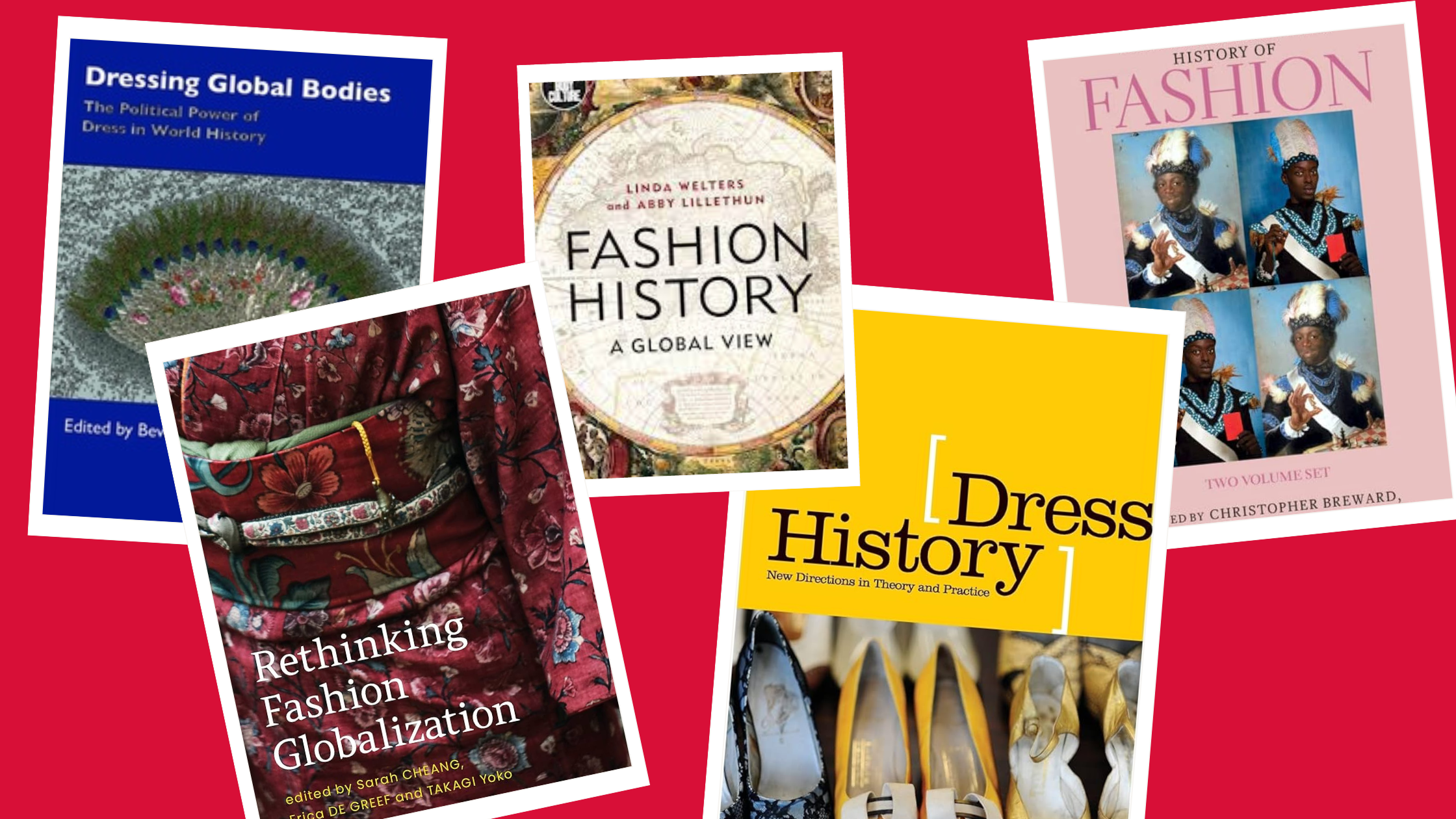

With that in mind, in this month’s Fashion in Focus, I’m sharing five books that might help us diversify the history of fashion:

1. The Cambridge Global History of Fashion — ed. Christopher Breward, Beverly Lemire and Giorgio Riello (2023)

Fresh off the press, this two-volume collection contains more than 40 essays that uncover thematic commonalities and the many transformations that have shaped fashion at a global level since Antiquity. The book is still on my reading list, not just because it’s massive but also because the two volumes cost more than $300. I do hope to get my hands on a library copy soon and I’m excited to read it because it claims to question the “origins” of fashion in modern Europe and focus on a variety of cultural “entanglements” that have shaped fashion around the world in and beyond colonialism. However, I am slightly frustrated by the apparent lack of focus on the Americas and Indigenous fashion practices, with only one chapter dedicated to “Fashion and First Peoples in European Settler Societies, c. 1700–1850” by Melissa Bellanta (vol. 1) and another dedicated to “Colonial Fashion Histories” by Karen Tranberg Hansen (vol. 2).

2. Rethinking Fashion Globalization — ed. Sarah Cheang, Erica de Greef and Takagi Yoko (2021)

This book studies the globalization of fashion as the result of “far-reaching cultural entanglements” (p. 1) that result from colonization, human migrations, and economic relationships. The aim of the book is to offer ways of “rethinking” global fashion in order to dismantle Eurocentric narratives that have shaped much of fashion history. Despite its global intent, which offers some very interesting case studies from Asia and a few from Africa, the Americas are notably absent from this volume. I find this absence quite curious, since I don’t think there’s a better example of the extent of early modern globalization than the Spanish Empire. As a result, I don’t think Eurocentrism in fashion can be fought without the inclusion of the Americas, especially Native Americans, in the writing of fashion history. However, the editors of the book do insist that it “is not an overview of fashion histories, processes or practices from around the world” but instead “asks how fashion topics rooted anywhere could be approached in less Eurocentric ways” (p. 4). This, I believe, is accomplished in different ways through the case studies introduced in each of the 13 chapters of the book.

3. Dressing Global Bodies: The Political Power of Dress in World History — ed. Beverly Lemire and Giorgio Riello (2020)

…when considered within such a global arena, dress is sometimes contentious, it brings together people as it sets them apart; dress is entangled with power and at times illuminates the persistence and defiance of marginalized peoples and displays the features of industrial and political systems whether in the making of new goods or the circulation of second-hand.

Lemire & Riello 2020, p. 1.

This book takes a material culture approach to global fashion in order to foreground cross-cultural exchange and the importance of creative actors that have been ignored in the writing of fashion history. Made up of 13 chapters, the volume argues that global fashion is necessarily political, especially in colonial and postcolonial contexts. This is one of the few fashion history books to include considerations about Native (North) American dress practices and their importance in the colonization of Turtle Island from the seventeenth century onwards. Other chapters focus on the dress of enslaved Africans, changes in clothing at the face of European expansion, and technological and material advancements resulting from cultural cross-pollination. However, like many other “global” histories of fashion, Latin America is virtually absent from this volume.

4. Fashion History: A Global View — Linda Welters and Abby Lillethun (2018)

The purpose of this book is to show that fashion history is a global cultural phenomenon, rather than a modern, Western, and mostly elite expression of culture. The book argues that “the problem of exclusion [in fashion history] can be solved by reconceptualizing fashion history as a global phenomenon” (p. 7), something it attempts to do precisely by going through the varied terms that have been used to denote “fashion” in and outside the Western canon. It also offers a sort of historiography that explains the dominance of Eurocentric narratives in the writing of fashion history. Finally, the book introduces different examples from around the world to demonstrate that fashion, in fact, is a global phenomenon and its history can (and should) be written at a global level. I have repeatedly assigned this book in the fashion history and fashion studies courses I teach precisely because of its clear focus on the need to change the fashion history paradigm.

5. Dress History: New Directions in Theory and Practice — ed. Charlotte Nicklas and Annebella Pollen (2015)

This book consists of 12 essays that collectively “argue that dress is a fundamental means, indeed sometimes one of the only available ways, by which groups and individuals express and negotiate their identities” (p. 1). The book offers a variety of case studies that span the past four centuries and different global contexts, aimed at illuminating on the methodologies and questions that should guide the writing of fashion history into the future. Importantly, the book offers some excellent examples that bridge theoretical rigor with the material study of clothing, acting as a model for ongoing research in fashion studies.

***

While none of these books offers a definitive alternative to otherwise Eurocentric fashion history narratives (and most offer very limited views of global Indigenous fashion practices), I do see them as starting points that we can continue to build from. Do you have any additions to the list? Please drop your recommendations in the comment section.

Do you want to receive updates directly in your inbox? Subscribe to my newsletter!

Leave a Reply