Dear fashion thinkers,

I hope I’m not too late to join the buzz about “national dress” at this time of the year. The summer Olympic Games in Paris filled my little corner of the internet over the past few weeks and, in addition to my favorite equestrian showjumping content, I’ve also seen tons of images and information about other sports, athletes, and of course, fashion.

Like many others around me, I was lured by the pleasant distraction offered by the Olympics. But, as much as I enjoyed feeling like I had an excuse to separate myself from my research, the Olympics also brought me back into the depths of one of my longest-standing research topics: the creation and expression of national identity. (Though I must also credit my trip to Greece earlier this summer and my wonderful host Becky for initiating that spiral 🥰.)

No wonder why I almost feel like fashion was more central to the Olympics than the actual sports. And now that they are over—and I’m finally grounded in the same city for a full month—I had to join the ongoing conversation on fashion, sports, politics, and nationalism that emerged around the Olympics.

Business of Fashion and Vogue Business started to cover the close relationship between the fashion industry, the Olympic Games, and sports more broadly several months ago—though mostly around marketing and sales opportunities. With the beginning of the games, fashion journalist Amy Odell wrote that the Olympics were basically “one giant LVMH ad” that placed products from the different brands of the conglomerate pretty much everywhere. And throughout the Games, dozens (hundreds? thousands?) of articles popped up with styling tips, beauty hacks, and even nail inspiration borrowed directly from Olympic athletes.

All of this is interesting as a case study of the rampant consumerism in the contemporary fashion system. But there’s one topic that I’m more interested in: the construction, expression, and performance of national identity.

In a piece for Vogue Business, Bolivian fashion journalist José Criales Unzueta pondered whether patriotism still sells in fashion. He claimed that it is not the direct link with nationalism what makes clothing desirable to certain consumers but, instead, broader and more abstract associations with a specific cultural identity. He used Ralph Lauren as one of his examples of this symbolism, for the brand has constructed an all-American identity that “sells because it evokes comfort and pragmatism” without the need for more literal symbols, such as imprinting the American flag in every one of its products.

But beyond aspiration, product placement, and the commercial potential of certain brands, I think that the Olympics were a sort of looking glass into the global politics of identity. As people from all around the world came together to watch global sportsmanship, the Games became an important site for image-making that encapsulates many of our collective ideas about identity.

We could talk, of course, about the many comments on the bodies of athletes, which stemmed mostly from hegemonic ideas about gender and beauty. Take, for example, the many exchanges on what femininity should look like sparked by US rugby player Ilona Maher or Algerian, transgender gold medalist Imane Khelif. All of these conversations and observations necessarily participate in broader discourses about fashion and the body—or rather: what kinds of bodies are desirable (or not) in fashion.

But what about national identities? Could “Olympic fashion” also point to the power dynamics that shape contemporary geopolitics when it comes to national identity?

This question came about after seeing way too much coverage focusing on the uniforms worn by athletes to the Opening Ceremony in Latin American fashion blogs, the press, and independent media. Mexican fashion critic Guillermo Fonseca wrote about the “awful” (his word choice) combination of clichés about Mexican identity that were put together for the country’s uniforms, which ended up communicating nothing about Mexicanness. Colombian fashion stylist Cristian Baena wrote about the unfortunate choice of a trench coat, which seemed to be completely foreign to both Colombianness and the working-class context from which most athletes come from. Other local fashion journalists critiqued the use of the stereotypical “sombrero vueltiao” (a bi-colored straw hat representing the Caribbean region of the country), which was seen as an unnecessary “exotic” element for a rainy day in Paris.

While the Latin American uniforms were heavily criticized, the world seems to have picked its favorites. Mongolia’s outfits by Michel & Amazonka were praised for showcasing the richness of the country’s ancestral textiles traditions. Haiti’s collaboration with Haitian-Italian designer Stella Jean featuring Guayabera-inspired jackets and blue cotton—both showcasing the fashion heritage of the country. Multiple designer alliances to dress Team USA continued to build the casual allure that placed the country on the global fashion scene since the early 2oth century even despite an early gender-based controversy with Nike. And, of course, France’s luxury collaborations with Berluti for the Opening Ceremony, and Dior, Jacquemus, and other globally-renowned brands in other instances and spaces.

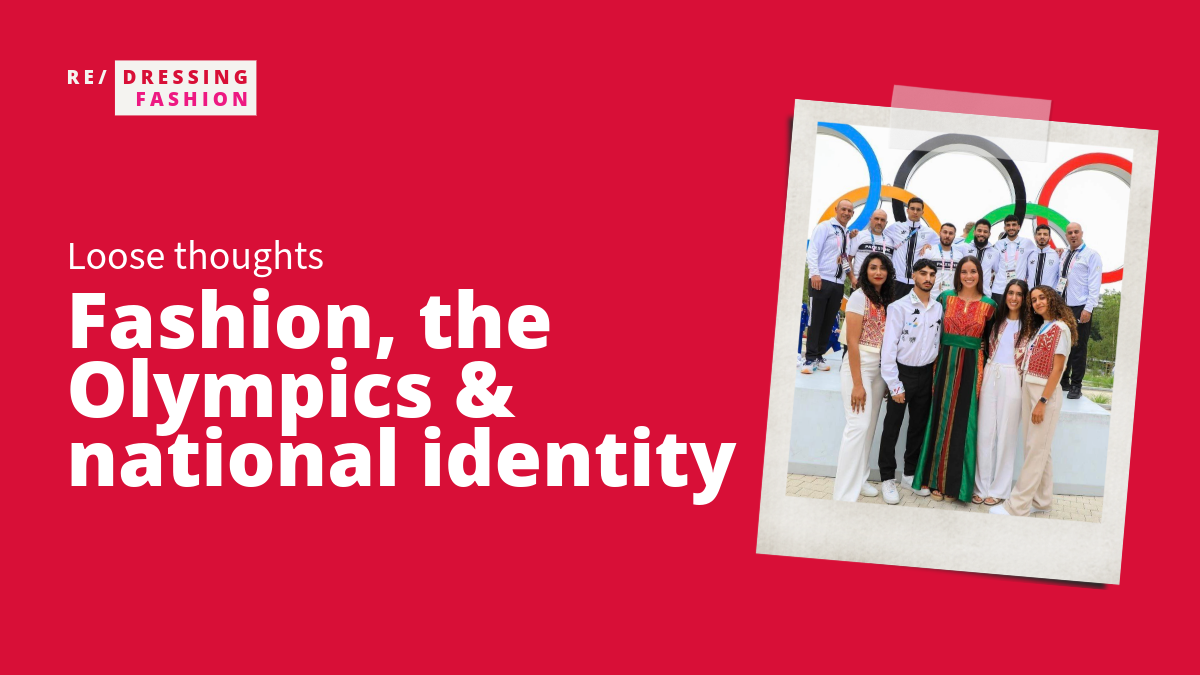

Less frequently mentioned but definitely important in today’s political scene was Palestine, whose small delegation made a political statement that went beyond the mere survival of Palestinian culture. Male athletes wore jackets with a black-and-white pattern recalling the keffiyeh, female athletes wore waistcoats with tatreez embroideries, and flag-bearer (and swimmer) Valerie Tarazi wore a thobe and keffiyeh wrapped around her head. But it was the other flag-bearer, boxer Waseem Abu Sal, whose outfit could win a prize in political fashion: with a shirt depicting the children who have been martyred since October of last year, approved by the Olympic Committee, he aimed to call attention to the current situation in his country and call for peace. Yet I don’t think we heard too much about him.

I realize that what I saw—or didn’t see—about “Olympic fashion” is totally biased by my interests, span of attention, the people I surround myself with, and of course internet and social media algorithms that know me too well. But I also want to say that the uniforms that we collectively chose to highlight and dismiss are reflective of broader dynamics in global fashion and the politics behind them.

Could the praise that Mongolia received be the result of our nostalgia for “ancestral” ways of being, making, and dressing, and an overall idea of a better past—just as we fail over and over again to actually slow down both fashion and our lifestyles? Was Haiti’s collaboration with Stella Jean valued only because she is one of the relatively few Black fashion designers to rise to global fame in Europe? Were France’s collaborations with luxury brands remarkable only because they reinforced the many myths about the origins of fashion in this country?

Now that I mention myths, I can’t help but state what seems obvious to me but somehow doesn’t always click: that national identities are precisely that (a myth). As a myth, they are rooted in a very specific, fabricated origin story that purposefully privileged some elements over others. And in the process, both external factors—like foreign views about our nations—and internal ones—including some unnecessarily glorified histories—are selected, refined, and brought together to construct what we think is a stable identity that endures over time.

The process of fabricating national identities has been taking place since at least the nineteenth century, when our contemporary nation-states started to take shape. The political context and many expressions of nineteenth-century nationalism in fashion have occupied much of my attention since I started writing my MA thesis almost 10 years ago. And this year I finally decided that I need to write more about it—but it won’t happen today.

As always, I promise to share more about this research when I’m ready. In the meantime, if you want to continue exploring the construction of national identity through fashion in the past 200(ish) years, please join my Redressing Fashion Book Club this month. We’ll be discussing one of my favorite book chapters about “fabricating specimen citizens” through clothing.

And if you have thoughts about fashion, the Olympics, politics, and national identity, please, please, please share your ideas by leaving a comment, reaching out to me on social media, or replying to my email newsletter. I’d love to know your thoughts!

Thank you for reading, watching, and joining the conversation.

Until next time,

—L 🩷

PS. Remember you can subscribe to my email list to receive blog updates directly to your inbox.

Leave a Reply