It’s print week in New York, meaning that these days are all about celebrating the art of prints in the city. So I decided to join the party and write about the most recent exhibition by the department of Drawings & Prints at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Fashion and Virtue: Textile Patterns and the Print Revolution, 1520–1620.

Although I was probably aware of the existence of prints before moving to New York, I started becoming increasingly attracted to them when I started to formally look at historical fashion and realised that prints were one of the very first media used for the diffusion of fashion trends—and, to a big extent, they still are. But when looking at all these historical prints of magazines such as Harper’s Bazaar or Le Mercure Galant, I started, slowly and steadily, falling in love with them. I’m a very detail-oriented person and big admirer of tasks that take long time to complete—possibly because I have no patience to engage in them myself—and this is probably what attracted me to the prints at the beginning. And then, as I started getting more and more into them, into the different techniques, their uniqueness—despite them being all prints—and their beauty, I couldn’t help but ending up obsessing about them.

So when I saw on the Parsons graduate course catalog for this semester a course named “Looking Closer: Drawings & Prints” I knew I had to take it.

Rather coincidentally, and only a week before my Drawings & Prints class began, I attended the Apollo Circle Benefit Committee launch party, and met Femke Speelberg, curator of Fashion and Virtue: Textile Patterns and the Print Revolution, 1520–1620, who invited me to the opening night of the exhibition. And then I found out that it would be the subject of my midterm paper for my Drawings & Prints class. So, as you might imagine by now, I’ve already seen it a few of times—and it’s only been on view for two weeks!

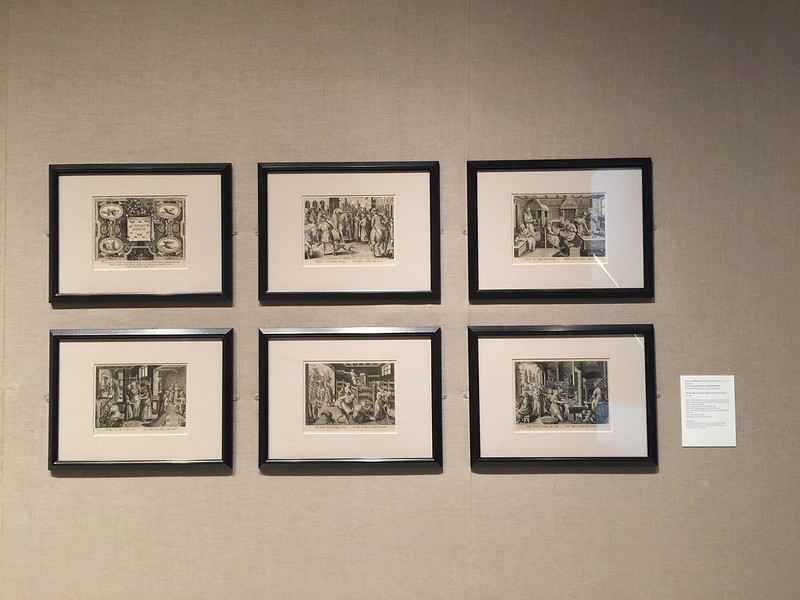

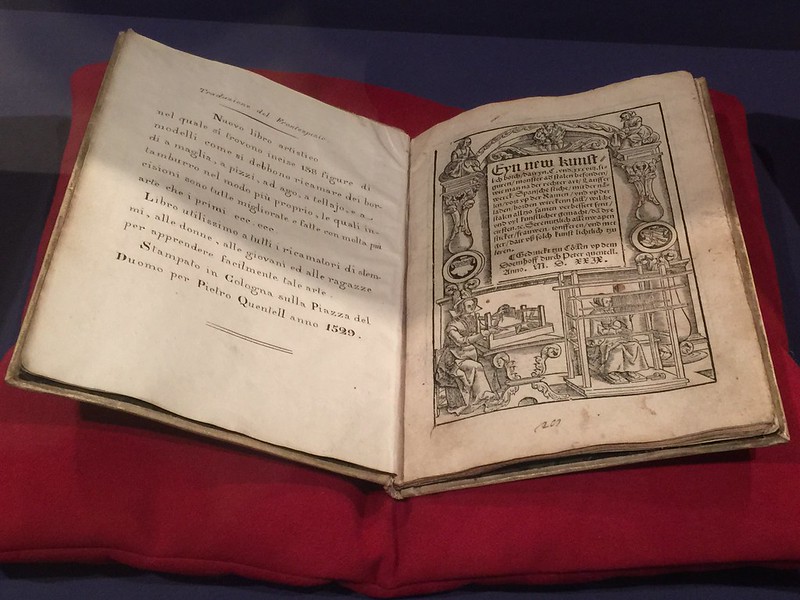

The exhibition explores the relationship between prints and the design of textile patterns during the Renaissance. The first expression of such a relationship appeared in a series of six woodcuts made by Albrecht Dürer, where he copied “knotwork” designs attributed to Leonardo da Vinci. Beginning with this move in the 1520s, the exchange of patterns, printed in small booklets, initiated what can be called today the first fashion publications. Rather than being intended to hide away in libraries, these books were meant to be used by people at different levels of society with interests in textile decoration, including women and young embroiderers. Many of them are now incomplete, illustrating that the tearing of pages to paste or nail them to workroom walls was a common practice, and the use of patterns similar to those found in Renaissance books in more recent garments suggests the importance of the impact of these early textile publications even today.

The main argument of the exhibition, if I get it correctly, is that this print revolution that started on the sixteenth century and shows an increasing amount of books of textile patterns published was the result of an increased production of fashionable textiles.

After centuries of economical lag during the Middle Ages, Europe saw in the Renaissance a re-emergence of commerce and trade, not only with the East—although this exchange had been happening for a while in Venice, with the Ottoman Empire—but between different places within the continent as well. As a result, the Renaissance brought a new form of exchange of products and ideas, and prints must have been a key factor contributing to it.

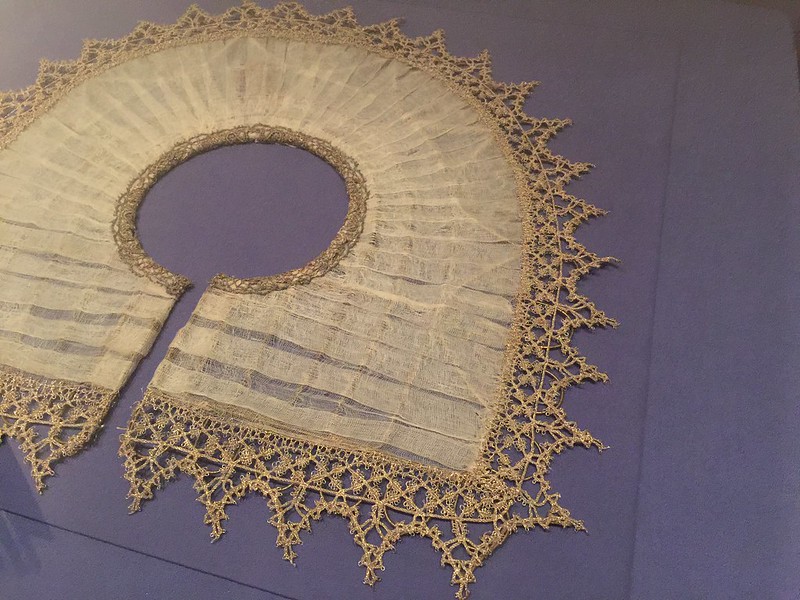

The Renaissance also saw the birth of certain centres of production of particular fashionable products, such as lace. Initially, these were located in Italy, but then moved to Flanders, where the most prestigious laces of the time could be found. But chances are that, unless you were member of one of the Royal Courts in Europe, you wouldn’t have had the possibility to even get near any of those. And here is where prints become essential, as they allowed the diffusion of lace styles and patterns throughout the continent, so that people were able to make them in the different countries and, in some cases, when the economic situation didn’t allow for more, even get them printed directly on fabric as a sort of faux-lace.

But this is something you definitely wouldn’t understand by just viewing the exhibition. I know it because I’ve studied world economic history for several years now and am on the second year of a master’s program in fashion history. I’m wondering what one of my non-fashion friends would get out of the exhibition—other than, of course, being extasied by the marvelous work in the actual prints and textiles shown.

Most importantly, what I couldn’t get at all was the “virtue” part of the exhibition title. The exhibition does include a section on the exhibition about the ideal of a virtuous woman and her relationship with needlework. Women were expected to be as virtuous as Virgin Mary, and acts related to needlework—spinning, sewing, embroidering, or knitting—were considered to bring them closer to the ideal than other passtimes like dancing or playing cards. And so publishers engaged in the proliferation of this ideal of femininity through the printing of books directed for women that were trained to become virtuous.

All of this makes sense, and might be, in fact, true: needlework, mostly for the patience it requires, has been used to describe the ideal passtime of the virtuous, virginal woman that has been promoted by most Western societies since the Middle Ages. But I still don’t understand fully how it links with the whole print revolution, or how it describes the entire exhibition, which includes early knotwork and later, twentieth-century adaptations of textile patterns commonly seen in sixteenth-century prints for textiles as well.

However, these are probably minor setbacks in the exhibition. Anyone that has ever been to a museum knows that there is not enough space in the walls to fully explain the history being told behind the objects exhibited. And if there were space to write more, I sincerely doubt people would actually read it and make an effort to learn it all. Only a few would. Which makes this exhibition a wonderful one, as all the objects shown are nothing but amazing!

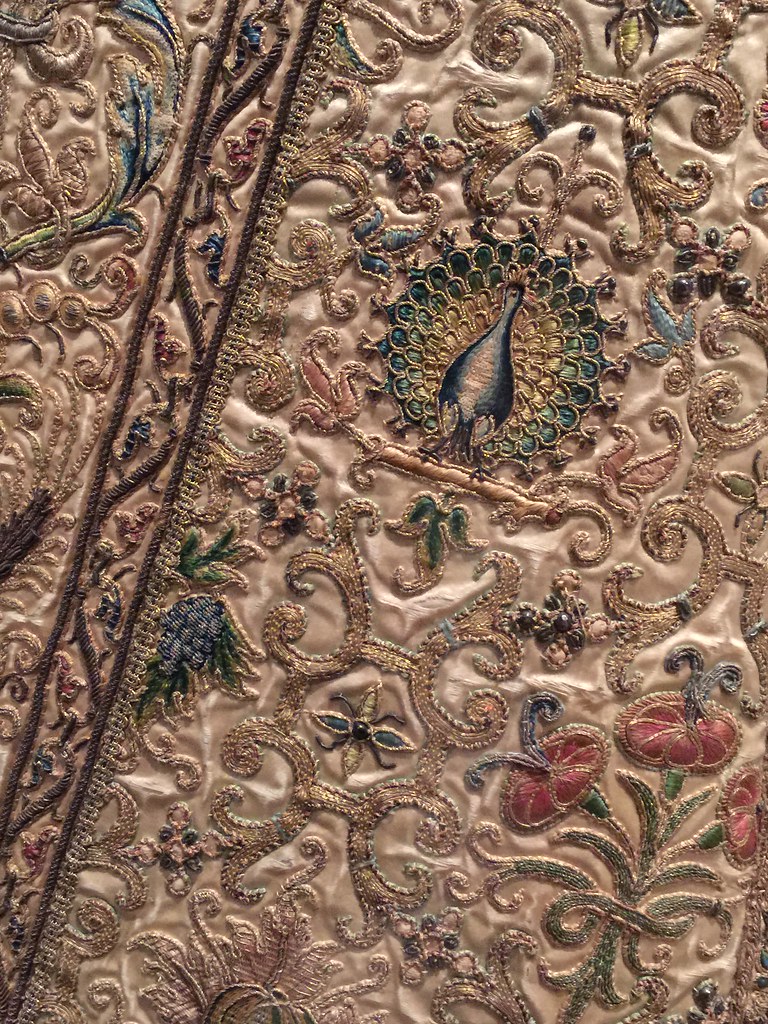

The collection is absolutely stunning. The prints are beautiful, and for those who might not be able to imagine what they would look like on fabric, the exhibition provides enough textile evidence to fill in that part of the imagination as well: not only are there printed patterns juxtaposed to the actual pieces of fabric, but the exhibition ends with a collection of more recent garments that show the importance of patterns in fashion design even today. There is also an actual woodcut from an interlaced design by Dürer—which absolutely made my life happier—together with the series of prints of such designs, as well as a beautifully embroidered chasuble—with peacocks and all!—that I would totally wear to class if I could.

So, as usual when it comes to the Met, I would recommend seeing the exhibition if you’re around before it closes next January. Even though I still am struggling with the title and some educational issues, you’ll definitely get to feed the eye and see some beautiful pieces of art.

Pingback:Lunelli